12 Acadian Folk Songs

Click titles to view texts

Acadian culture provides a rich tapestry of musical and storytelling traditions. This songbook of Twelve Acadian Folk Songs celebrates Acadian culture by showcasing its music and folklore. Aspects of the old and the new intertwine in these arrangements, and they are the result of a long and fulfilling collaboration with my cousin, pianist and interdisciplinary artist Carl Philippe Gionet. These re-imaginings are set in the aesthetic of 19th century Lieder or French mélodie, where voice and piano play equal solo parts within the musical architecture.

C. P. Gionet’s new arrangements of Twelve Acadian Folk Songs were originally conceived for my voice, however, this songbook is aimed at voice students and voice professionals alike. My extensive experience as a vocal educator and performer has shown me that voice students in Canada studying in academic and non-academic settings are encouraged to perform Canadian musical content and explore diverse musical styles. This songbook of Twelve Acadian Folk Songs provides a valuable educational and performance resource, as the songs feature necessary aspects for the development of voices, such as lyrical vocal lines, strong storytelling, Canadian minority language and culture, and complexity of the piano part. The folk song arrangements feature a musical cross-genre approach and are written in a style that facilitates the development of a healthy vocal technique, so they will appeal to international voice communities as well. This first publication of the songbook is in a medium tessitura that suits all voices, and the song narratives enable all genders and voicetypes to freely interpret these stories. The song narratives contain universal themes that transcend time, gender, ethnicity, and socio-economic structures. These themes explore love and parting, loss and conflict, epic journey, and whimsical nonsense, and simply how to make sense of the world. I believe that everyone can find a small part of themselves within these stories, and that all singers can make them their own.

C. P. Gionet’s approach to the Acadian folk song arrangements is rooted in the oral tradition, where music and texts are passed orally from generation to generation, without the use of musical notation. He selected folk songs that were already committed to his memory, passed on to him orally from family members and childhood musical activities. In the arrangements, C. P. Gionet has remained as faithful as possible to his musical memory. He has also taken liberties with the traditional texts, often re-working the order of the storytelling, making omissions, and creating repetitions to enhance the dramatic arc of the pieces.

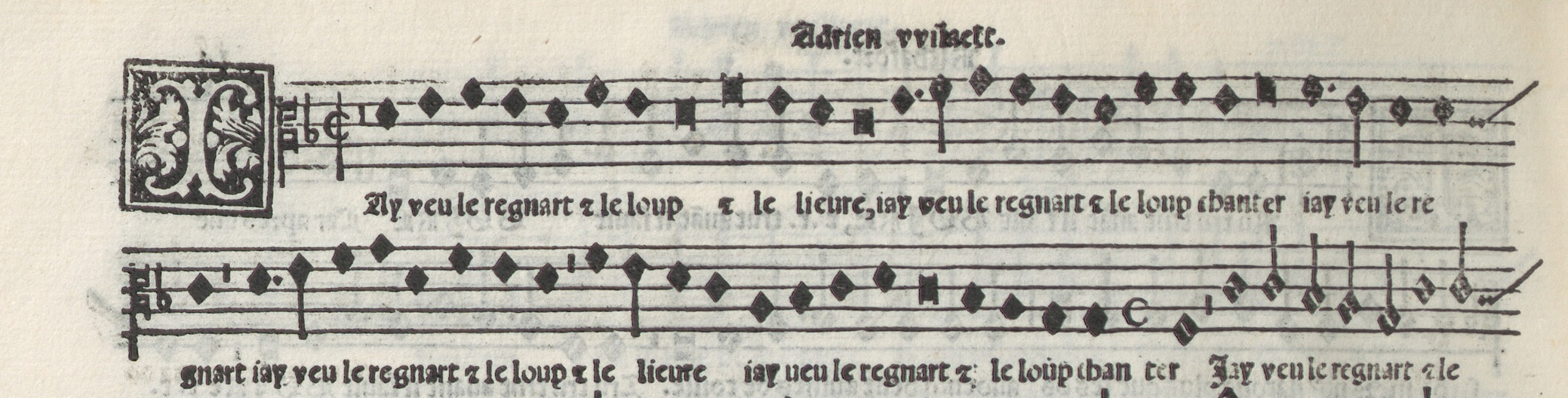

Some dramatic themes and musical structures from Acadian folk songs can be found within the chanson tradition, which can be traced back to the Middle Ages. In the folk tradition, the texts for the choruses, or refrains, can exist as separate entities. The same refrain can appear in different songs, and the same song can appear using a different refrain. The verses contain the narrative, while the refrain can interrupt the story with text that is completely unrelated to the drama. This style is heard in many of the Acadian folk song arrangements featured in this song collection. For example, here we can see the refrain from “L’escaouette” appearing in an older song printed in Venice in 1536, that could be its first notated version.

J’ay veu le regnart et le loup et le lièvre,

J’ay veu le regnart et le loup chanter.

Used with permission by the Department of Music of the Austrian National Library (SA.78.C.27/2, f. 14v)

However, most of the songs in the compilation developed later in time. For example, “Partons, la mer est belle”, a much-loved song from Acadian culture originates in the popular songs of France in the 1800s, and the foundations of its text then took shape in France during the 1900s, as shown by two field recordings dating from 1967 and 1986, sang in Île d’Yeu (Vendée, Pays de la Loire). When we examine another song featured in Twelve Acadian Folk Songs, “Au chant de l’alouette”, we can see how its text has developed, when compared with an earlier version called “Quand j’étais chez mon père”:

Au chant de l’alouette (modern version)

Mon père m’envoie-t-à l’arbre c’est pour y cueillir

Je n’ai point cueilli, j’ai cherché des nids.

Au chant de l’alouette, je veille et je dors

J’écoute l’alouette et puis je m’endors

J’ai trouvé la caille assis sur son nid ;

J’lui marchai sur l’aile et la lui rompis.

Elle me dit « Pucelle, retire-toi d’ici! »

– Je n’suis pas pucelle, que j’lui répondis!

Quand j’étais chez mon père (older version, 1896)

Quand j’étais chez mon père, enfant petit,

Gle m’envoyit aux landes chercher daus nids.

T’endores-tu, Jeanette? O lon la la,

T’endores-tu, Jeanette? Oh! que non jà!

I en trouvis un de caille, deux de perdrix ;

Montit dessus son aile, grand mal lui fit.

– « Petite pucelette, tu me détruis ».

– Petite pucelette, je n’la suis pas.

Song gathered by Trébucq (La chanson populaire en Vendée, 1896, p. 148-49), sung in poitevin by Madame Cardineau de la Roche-sur-Yon (Pays de la Loire).

The title of “Au chant de l’alouette” comes from the fixed refrain, which is always the practice in contemporary popular music. However, in “Quand j’étais chez mon père”, the title comes from the first line of the text, as was common in the Middle Ages and Renaissance. This older version is sung in the poitevin dialect, which has links to the French spoken today in Acadie. It’s also interesting to note that both “Au chant de l’alouette” and “Partons, la mer est belle” have origins in the Vendée region in France’s Pays de la Loire. Many aspects of the texts in both versions are similar, although the refrain of “Au chant de l’alouette” has more direct links to another song that originated in the theatrical drama Pougatscheff performed in Paris in 1853. Its refrain is sung by the character Tartanac who performs a “romance from Gascony” (Act II, 6th tableau, scene 6), a region close to Pays de la Loire:

Quand j’étais chez mon père, enfant petit,

J’allais dans la bruyère chercher des nids.

Au chant de l’alouette, je veille, je dors,

J’écoute l’alouette, et je m’endors!

Pougatscheff : Épisode de l’Histoire de Russie, 1853. Albert and Labrousse (libretto) / Fessy (music) / Honoré (ballets). Melodrama in 3 acts and 14 tableaus. Premiered in Paris June 21, 1853. (Paris: Dechaume, 1853, p.16)

By examining the journey of one song, “Au chant de l’alouette”, we can see how texts can develop in the synergetic folk music tradition. C. P. Gionet and I are excited to contribute to the evolution of these songs of Acadie, and we invite you to join us on the journey!

A recording of Twelve Acadian Folk Songs is on the album “Tu me voyais” featuring C. P. Gionet and myself as performers, released by Leaf Music and NAXOS. The recording provides a valuable resource for those using the scores in professional and educational settings.

— Christina Raphaëlle Haldane

Contributors: Carl Philippe Gionet and Patrice Nicolas

Copy Editors: Jill Rafuse and Patrice Nicolas